On the first day of spring, officially the happiest day of the year, thanks UN and Pharrell, my partner and I celebrated our daughter’s first birthday.

The night before, after staying up late watching an Oscar-worthy, iPhoto-produced, slideshow of the previous year, I thanked my partner for bringing new life into the world, adding that it was the most selfless and powerful thing I’d witnessed.

After the wine was gone, we turned in with the laughter that guides us to bed most nights. I half-joked that wherever and whenever there is an important decision to be made, or a conflict to be resolved, from war to what beer to buy if any, one should simply raise both arms as if surrendering, and callout for any nearby mother’s consult.

Freudian analysis aside, I was serious. This past year I have been both humbled and inspired as a witness to childbirth and motherhood. Through this example I’ve learned that making life easier has nothing to do with selfishness, rather, it has everything to do with attempting to personify the selflessness my partner embodied those laborious fourteen hours that bridged winter to spring.

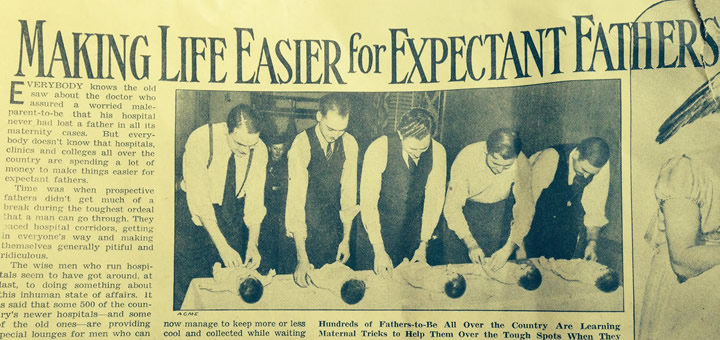

So imagine my chagrin when I stumbled upon an article from 1940 titled Making Life Easier for Expectant Fathers that solely focused on making childbirth easier for fathers-to-be. It started with a joke “about a doctor who assured a worried male-parent-to-be that his hospital never had lost a father in all its maternity cases.”

Five Flashback minutes later, I had learned that there was once a “time when prospective fathers didn’t get much of a break during the toughest ordeal that a man can go through.” Thankfully, according to the article however, “men who once paced hospital corridors, getting in everyone’s way and making themselves generally pitiful and ridiculous,” could now, because of other “wise men who run hospitals,” be taken care of. “Almost,” as one hospital administrator put it, “as if they were patients themselves.”

Suffering dads all across the country were finally being provided “special lounges” where they could “relax in overstuffed chairs, chain smoke and have paternal conversation with other men in the same predicament.” If they got hungry or thirsty, there were drug stores nearby where they “could gulp sandwiches and enjoy cool drinks.”

At one particularly forward-thinking hospital in Minneapolis, a father-to-be was provided his own “air conditioned, sound-proofed room,” where a personal nurse would make sure he didn’t “need medical attention, a sedative or a soothing word.”

The article closed by excusing these new comforts for expectant fathers, insisting that surely “no one begrudges” “American husbands” for them. Easily switching the tone from misogynistic to racist-light, the author expounds, “After all they aren’t quite as bad” as other “head-hunting men in Ecuador that ask their wife to go outside the hut and have the baby as quickly and quietly as possible while he reclines inside.”

Although I’m a fan of air conditioning and sedatives, those are the last things that would have made things easier for me as an expectant father.

Reactive and befuddled by the yellowed article, I threw my arms up and complained to my partner about how messed up fathers must have been in the 40s for making things easier by removing themselves from the miracle I witnessed a year ago.

After listening to me and validating how I felt, she sympathetically pointed out that in the 1940s mothers weren’t present during labor either. They were put under general anesthesia to give birth; a far worse way that things were made easier back then.

- A Very New Pickathon in 2022 - August 13, 2022

- Pickathon returns to Pendarvis Farm! It’s not just the artists that’ll be new. - August 3, 2022

- July is BIPOC Mental Health Awareness Month (Black, Indigenous, Persons of Color) - July 14, 2022

OMG. Especially pertinent after today’s criticism of Mets 2nd baseman Daniel Murphy for taking three days paternity leave. This seems to be precisely the period NY talk show host Mike Francesa is from.